|

|

|

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

Sunday, October 8,

2000

Help Wanted: Elite

Musicians

The L.A. Philharmonic has

filled a dozen openings by putting hopefuls through a rigorous audition

process.

By JOHN HENKEN

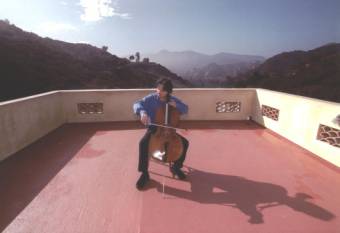

Shulman, L.A. Philharmonic Principal Cellist, at his

home in the Santa Monica Mountains.

In an

election year, some pundit inevitably labels the U.S. Senate the "world's

most exclusive club." But major U.S. cities have clubs of similar size

that are even tougher to get into--their symphony orchestras.

Certainly the talent-and-training bar

appears to be much higher in an orchestra. But while the qualifications

may seem more objective, ultimately the symphonic hopeful is chosen by the

same elusive standard as the political candidate--be the one we want.

An unusually large number of Los Angeles

Philharmonic members have been recently elected, due mostly to

retirements. The ensemble that just launched the new season has a lot of

new faces. The orchestra has filled 12 positions--more than 10% of the

work force--since the end of the 1998-99 season, bringing close to 1,000

auditioning hopefuls to Los Angeles.

Newest of the Philharmonic newbies is

principal cellist Andrew Shulman. His first concert with the orchestra was

just a week ago, a preseason community event in Pasadena, with music

director Esa-Pekka Salonen on the podium. A mainstay of the London music

scene for the past two decades and a British citizen, he has been solo

cellist for the Academy of St. Martin in the Fields and the Philharmonia,

and was cellist of the much-recorded Britten String Quartet for 10 years.

In 1990, Shulman won the Piatigorsky

Artist Award, a prestigious invitational competition at the New England

Conservatory of Music, which carries attendant teaching and recital

engagements. He has also been developing a parallel career as a conductor,

and anticipates returning regularly to Europe to work with orchestras in

Ireland, England and Scandinavia.

For

all of that, the move to Los Angeles is hardly a provincial retreat. The

Los Angeles Philharmonic's reputation in Europe, Shulman says, "is very

high, very fine." He is talking by phone amid moving-in debris at his new

house in Topanga Canyon.

"The

Philharmonic has a stability a lot of other American orchestras don't

have," he says, explaining why a Brit might uproot his family and move to

America's West Coast. "Esa-Pekka has a real vision of what the orchestra

should be. He has a good relationship with the orchestra, so you don't

have the politics and shenanigans you get in other orchestras."

Shulman comes by his talent naturally

enough; his father was a double bass player and his mother was an opera

singer. He began piano lessons in a desultory fashion when he was 6,

before starting the cello at age 10.

"I

chose cello partly because my father could help me with it, but there was

also something about the sound of the cello. Its range is that of a human

voice and it seemed more natural to me than violin. Once I got hooked on

cello, that was it."

He was also hooked

on orchestras. At 19, straight out of the Royal College of Music, he

joined the Halle Orchestra. About a year later he became solo cello with

the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic and the Academy of St. Martin in the

Fields. Then, at 22, he became solo cello of the Philharmonia Orchestra.

He devoted seven years full time to the Britten Quartet, but reenlisted in

orchestra playing in 1994 when "the Philharmonia made me an offer I

couldn't refuse to come back."

Although

he has played concertos and recitals throughout his career, he has no

reservations about his preference for orchestral playing over solo work.

"It's the repertoire, definitely,"

Shulman, now 40, says. "At an early age, I devoured scores. I've always

been interested in orchestration and structure, which is why I am now

doing more conducting. There is nothing I enjoy more than getting into the

style of a composer and the shape of a piece of music."

Shulman met Salonen through his work

with the Philharmonia, where the conductor has been a regular guest. It

was Salonen who invited him to apply for the principal cello chair here.

"I think the Philharmonic got to the

stage in the auditions where they had not found anyone whom everyone could

agree on. I've known Esa-Pekka a long time, and he suggested I come. I

came and played with the orchestra for a week and I enjoyed the atmosphere

very much.

"Interestingly, Esa-Pekka is

very different with the two orchestras, a very different personality.

Which says a lot about him, that he can adapt to and is sensitive to the

instrument he is conducting.

"It was a

long process then, bringing my family over to check out schools and

houses. We're very pleased to be here now."

As a result of those visits, Shulman,

his wife and two children settled in Topanga, allowing them to indulge a

passion for dogs and walking. He is also "just getting into surfing."

"We were looking for something not too

cityish," Shulman says. "It is a bit of a commute, but I did something

similar in England, driving in from the country."

"I have known Andrew since 1983,"

Salonen says. "Before I picked up the phone and called him, I thought,

'Maybe he has done London now, maybe he is ready for a change.' It seems I

was right.

"He is very versatile, very

warm and passionate in his approach to his instrument and to music-making.

We are pleased to see how easily he has fit in. Very clearly, the

personality dynamic here is good."

* * * The process of filling

jobs at the Philharmonic always begins with an advertisement in the

International Musician, the monthly paper of the musicians' union. The

applications pour in--usually hundreds for each position--and the

Philharmonic's Auditions and Renewals Committee culls the pile to 40 to

150 candidates for each opening who are invited to audition here.

"We used to do taped applications as

well, but no longer, just because with technology now it is so easy to

mess with recordings," says Gail Samuels, the Philharmonic's orchestra

manager. "The preliminary [rounds are] played from behind a screen,

without the music director present. The players are usually asked for a

bit of a concerto and a lot of excerpts [from specific works in the

symphonic repertory]."

The committee,

expanded with members of the pertinent section, then votes on advancing

the player to a semifinal round, which is also played anonymously--the

better to ensure equal opportunity.

In

the final round, however, all is revealed.

"The screen comes down and the music

director comes in," says Samuels. "People play much longer here, maybe 15

to 20 minutes. There is discussion, of course, and then the committee

votes to qualify one or more of the finalists, and then the music director

chooses. He can also invite them to play with the orchestra for a week.

Everyone's goal is to get the best player."

If the fit isn't right, as happened in

the search for a principal cellist, more proactive recruiting takes place.

"We basically felt that the kind of people we were interested in would

have to be invited," Salonen says. "Obviously, in real-life situations,

you can't ask experienced and busy artists such as this to come and play

behind a curtain. They come and play with the orchestra for a week, maybe

give a recital."

The experience of

Tamara Thweatt, a piccolo player who started her Philharmonic career in

July with the beginning of the Hollywood Bowl season, is more typical. A

recent graduate of the doctoral music program at the University of

Michigan and a freelancer in the Flint and Ann Arbor symphonies, she

spotted the ad in the union paper, sent in her resume, and was one of 100

chosen to begin the auditions.

"The

Philharmonic has a wonderful policy of inviting many people to come," she

says. "I flew to Los Angeles at my own expense to take the

audition--fortunately, I have a sister who lives in Pasadena. The

auditions were played in four rounds over two days, taking us from 100 to

20 to seven to four players. Everyone was very professional and kind--I

always had a room to warm up in.

"By the

end I was really tired and hungry, but it was so amazing. I have been

auditioning for about eight years, seeking a job in a full-time orchestra,

basically applying anywhere there was a position open. How honored I am,

being in such a wonderful place, with such an orchestra!"

Thweatt may not come to the Philharmonic

with the same level of orchestral experience that Shulman does, but she

shares his reasons for choosing the symphonic life.

"The repertoire is just so beautiful.

The piccolo doesn't play all the time, and I enjoy just listening. It is

so lovely, being right there in the middle of a group with so many colors,

so much wonderful playing."

* * * In addition to Shulman

and Thweatt, other newcomers to the Philharmonic over the past season

include violinists Chao-Hua Jin, Akiko Tarumoto and Jonathan Wei; violist

Hui Liu; cellists David Garrett and Brent Samuel; bassist David Allen

Moore; oboist Anne Marie Gabriele; French horn player Bruce Hudson; and

associate principal trombone James Miller. Still open is the principal

trumpet chair and, with the recent retirement of pianist Zita Carno, the

keyboard position.

"It is unique in the

Philharmonic history--and for almost any orchestra--to add this many new

players," Salonen says. "The standard is very high in this country. There

are some really fantastic people out there, so in that sense it was very

difficult.

"It is an interesting

balance. When a young player comes to an orchestra, the process usually is

that they adjust their style to fit in. But when hiring, I also try to

imagine what they can add, how they can continue in our tradition but also

contribute new energy. The change in an orchestra is gradual over time, an

organic development, but change is necessary. An orchestra has to be

constantly self-critical and evolving."

With a Hollywood Bowl season behind her,

Thweatt already knows something about fitting into her Philharmonic role.

"At the beginning in July, the pace of

things was very challenging, having only one rehearsal per concert," she

says. "But I was sent all the music ahead of time, and the librarians and

other musicians were all extremely helpful. I got tired midway through,

but I also learned so much in so short a time. It has given me a lot of

confidence for the fall season.'

Shulman, with the depth of his

experience, will be expected to take a leadership role right from the

start. In addition to playing the solo parts that come along and more

mundane tasks such as enforcing common bowing patterns, section principals

such as Shulman must take much of the responsibility for creating and

maintaining the signature sound of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which he

defines as having "definite warmth, like European orchestras, but also

more precision and depth."

"For some of

the key positions, we have to consider not only instrumental skills, but

also personality and leadership," Salonen says. "Auditions are more

complicated than just listening. In particular, to find somebody to

succeed [retired principal cellist] Ron Leonard, who is such a great

musician and so respected by all the orchestra, it is a weighty decision.

Out of all the people we invited, we thought Andrew made the best solo

cellist."

"I consider my job more to

create an atmosphere and a sound that people can play into and contribute

100%," Shulman says. "You have to have a vision of what you want the

section to sound like."

John Henken Is a Regular Contributor to

Calendar

Copyright 2001 Los Angeles Times

|

|

|

|

|